“What we are now doing to the world… by adding greenhouse gases to the air at an unprecedented rate… is new in the experience of the Earth. It is mankind and his activities which are changing the environment of our planet in damaging and dangerous ways.”

“We all know that human activities are changing the atmosphere in unexpected and in unprecedented ways.”

The Primer

Starting Point — Global Warming 1-2-3: For all the arguments you may hear in the media, the basic science of global warming starts with two simple facts that lead directly to one simple conclusion:

- Fact 1: Carbon dioxide (and other “greenhouse gases”) trap heat and make Earth warmer than it would be otherwise.

- Fact 2: Human activity such as the burning of fossil fuels (coal, oil, gas) is rapidly increasing the amount of carbon dioxide in Earth’s atmosphere.

- Inevitable Conclusion: We should expect the rising carbon dioxide concentration to warm our planet, with the warming becoming more severe as we add more carbon dioxide.

The logic above seems rock-solid, but of course logic alone is never good enough in science. We need to establish that the “facts” are really facts, and that the seemingly inevitable conclusion is actually backed by evidence. In the rest of this primer, I will show you the indisputable evidence behind the two facts and conclusion. At the end, I’ll confront some of the “skeptic” arguments head-on. If you harbor any doubts at all about the science of global warming, I hope you will read all the way through. Let’s begin with some Q&A relating to the starting point argument above.

Question 1: In the starting point above, “Fact 1” claims that a higher atmospheric concentration of carbon dioxide will make Earth warmer. Is there any doubt that, all other things being equal, higher carbon dioxide concentrations do indeed make planets warmer?

Answer: No doubt at all. The basic mechanism by which carbon dioxide and other “greenhouse gases” (including water vapor and methane) heat planetary atmospheres is called the greenhouse effect. This mechanism was first demonstrated in the laboratory more than 150 years ago (!), and is so well-tested and well-understood that you will not find any scientists who dispute it. (For those who are interested, Figure 1 below shows how the greenhouse effect works.) In fact, the greenhouse effect occurs naturally on Earth, and that turns out to be a very good thing: Without it, Earth would be far too cold for liquid water or life. Studies of other planets show that the greenhouse effect can be even more important in determining a planet’s surface temperature than the planet’s distance from the Sun. Venus provides the most extreme example: Although Venus is closer to the Sun than Earth, its clouds are so reflective that less sunlight reaches Venus’s surface than Earth’s surface. As a result, without the greenhouse effect, Venus would be colder than Earth. But because Venus has a thick atmosphere containing far more carbon dioxide than Earth’s atmosphere (by a factor of about 170,000), Venus’s actual surface temperature is a searing 870°F. Given that the naturally occurring greenhouse effect is a good thing for life on Earth, Venus offers proof that it’s possible to have too much of a good thing.

Key point for Question 1: Scientific understanding of the greenhouse effect is tested and verified, not opinion. Planetary temperatures expected without the greenhouse effect can be simply calculated because they depend only on distance from the Sun and the percentage of sunlight that is absorbed rather than reflected; planetary temperatures expected with the greenhouse effect can be calculated by also including effects due to the measured amount of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. The temperatures calculated with the greenhouse gas contribution match the actual temperatures of the planets, demonstrating that we do indeed understand the greenhouse mechanism very well.

Figure 1. This diagram shows the basic mechanism of the greenhouse effect, which makes Earth warmer than it would be otherwise. Earth’s surface absorbs energy from visible sunlight, and returns this energy to space in the form of infrared light. Greenhouse gases (such as carbon dioxide, methane, and water vapor) slow the escape of the infrared light, thereby keeping the surface and lower atmosphere warmer than it would be otherwise.

Question 2: In the starting point above, “Fact 2” claims that human activity has been raising the concentration of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases in Earth’s atmosphere. Is there any doubt about this fact?

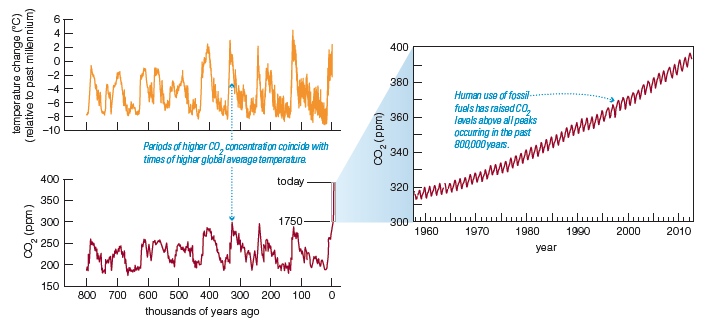

Answer: No doubt at all. Figure 2 shows the carbon dioxide concentration over the past 800,000 years (and probably more than it has been for at least several million years), along with corresponding data for temperature variations. Data since 1958 (shown in the inset at right) are direct measurements of the atmospheric carbon dioxide concentration, while the older data come from study of air bubbles trapped in Antarctic ice core samples. Notice that the carbon dioxide concentration shows natural variations ranging between about 180 and 300 parts per million (ppm), and that these variations clearly correlate with Earth’s global average temperature. The clear concern is this: In recent decades, the concentration has skyrocketed to more than 400 ppm, making the current carbon dioxide concentration far higher than it has been for at least 800,000 years. The timing of this rise makes it fairly obvious that human activity is responsible for it, but there’s additional evidence that makes it even more certain that the rise is due to us: The isotopic composition of the carbon in fossil fuels is slightly different from that from other sources, and careful measurements leave no doubt that the added carbon dioxide is coming largely from the burning of fossil fuels. The same is true for other greenhouse gases, such as methane; carbon dioxide gets the most attention because it is the most common greenhouse gas released by human activity (and because it can remain in the atmosphere for the longest time), but it is important to pay attention to other greenhouse gases as well.

Key point for Question 2: There is no doubt that human activity is adding carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases to the atmosphere. Today’s carbon dioxide concentration is already some 40% higher than it was at the time of the American Revolution, and at its current rate of increase will reach double its pre-industrial level by around 2060 to 2070.

Figure 2. This diagram shows the atmospheric concentration of carbon dioxide and global average temperature (relative to the average for the past 1,000 years) over the past 800,000 years. Data since 1958 come from direct measurements at Mauna Loa; click here to see the latest data. Earlier data come Antarctic ice cores. You may also wish to see the animated version of this graphic produced by NOAA.

Question 3: In the starting point above, the “inevitable conclusion” indicates that we should expect the rising carbon dioxide concentration to be warming our planet. Does the evidence show that such warming is really happening as expected?

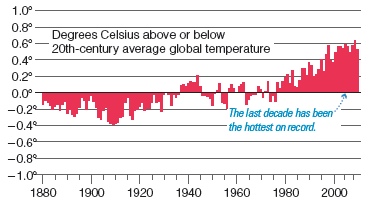

Answer: Yes. For the past several decades, we’ve had satellite data from which to make measurements of Earth’s global average temperature. Data from earlier times were local rather than global, which means there are greater uncertainties in converting them to a global average. However, by studying a great variety of data sources (ranging from newspaper temperature reports to natural records like those in tree rings), the uncertainties have been reduced enough to make the trend quite clear. Figure 3 shows the results: The global average temperature has increased about 0.8°C (1.4°F) in the past century, and the long-term trend is clearly upward.

Key point for Question 3: Data clearly show that Earth’s global average temperature has warmed about 0.8°C (1.4°F) in the past century — supporting the basic logic of the global warming 1-2-3 argument above.

Figure 3a. This graph shows changes in Earth’s global average temperature (in Celsius degrees) since about 1880; the zero line is the average for 20th century. Uncertainties are not shown, but range from about 0.3°C for the earliest years (left) to less than 0.1°C for recent years. Based on data from NOAA.

Figure 3b. This video from NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies (GISS) shows the changes distributed on a global map, illustrating that while local temperatures can vary significantly, the global trend is very clear.

Question 4: OK, so there’s no doubt that carbon dioxide raises a planet’s temperature, that we’re increasing Earth’s carbon dioxide concentration, and that Earth is already warming. Still, couldn’t the recent rise in temperature be due to natural variability, rather than human activity?

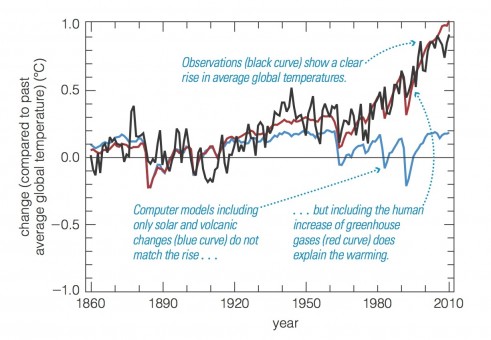

Answer: The only way to know for sure whether the temperature rise is natural or due to human activity is to perform experiments in which we compare what would happen on Earth with natural factors alone to what would happen when humans are included in the equation. Of course, we don’t have two Earths to compare, so we use computer models to make “simulated Earths.” Modeling inevitably involves uncertainties, but if a model fits data well, then we can have confidence that it is on the right track. Figure 4 shows actual temperature measurements in black. The blue curve shows model predictions based only on natural factors, while the red (or brownish-red) curve includes the human contribution to the greenhouse gas concentration. Note that both models (the one based on natural factors only and the one that also includes the human contribution) match the actual data reasonably well before about 1950. But for the past few decades, the models that include only natural factors fail quite miserably, while the models that include the human contribution continue to match the actual data.

Key point for Question 4: Climate models will never be foolproof, but current models match past data quite well and offer strong evidence in support of the claim that human activity is the primary cause of recent global warming. When you couple this evidence with the rock-solid foundation of the global warming 1-2-3 argument given above, it becomes difficult to imagine any other explanation for the observed warming.

Figure 4. This graph compares observed temperature changes (black) with the predictions of climate models that include only natural factors (blue) and models that also include the human contribution (red). Only the models that include the human contribution to the greenhouse gas concentration match observations well. Note: For a brilliant look at the individual components of the models shown on this graph, go to http://www.bloomberg.com/graphics/2015-whats-warming-the-world/.

Question 5: So how is that I can turn on the news and still hear some scientists claiming that we needn’t worry about global warming?

Answer: First of all, these scientists are extremely few in number. Surveys have found that at least 97% of scientists who have studied global warming are convinced that it is a serious and imminent threat to our future. Second, even among the less than 3% who count themselves as “global warming skeptics,” there is still no dispute over any of the facts I’ve given above. In other words, even these skeptics concede that carbon dioxide warms planets and that human activity is raising the carbon dioxide level, and therefore that without a change in human emissions of carbon dioxide, significant global warming will eventually occur. Their so-called skepticism comes from a belief that current climate models are overestimating the rate at which global warming will occur, and therefore that we have time before we need to take drastic or expensive action. The problem with this belief is that, in order for the climate models to be overestimating the warming effects, they’d have to be missing some feedback process than can mitigate global warming. But if that were the case, then we would not expect the models to work very well at reproducing actual climate data — and as you can see in Figure 4, they work very well indeed. This fact explains why the vast majority of scientists reject the “skeptic” argument.

Key point for Question 5: No real scientists, not even the so-called “skeptics,” disagree that Earth will eventually experience severe global warming unless we limit the continued emission of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. The skeptics simply claim that we have more time before things get bad than the “consensus” scientific opinion. So think about it this way: Imagine that you consulted 100 doctors about a tumor, and 97 of them said you need surgery and treatment, while 3 said they agreed your tumor was potentially dangerous, but felt you could safely leave it alone. What would you do? Given that 97% of scientists say we need to deal with global warming now while only 3% say we have time to waste, you should make your decision on global warming in exactly the same way.

Question 6: What kinds of consequences can we expect from global warming?

Answer: The short answer is that all the recent trends we’ve experienced — particularly the more extreme weather and increased polar melting — will continue to get worse. More specifically:

- The same models that successfully match past temperatures predict that, if we do nothing to slow our emissions of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases, the current warming trend will accelerate; by the end of this century, the global average temperature will be 6°F to 10°F (3°C to 5°C) higher than it is now.

- Although a temperature increase of a few degrees might not sound so bad, regional changes in climate patterns can be much more dramatic. Polar regions will generally warm more than equatorial regions, leading to increased melting of polar ice. The amount and distribution of global rainfall will change, with the potential for major disruptions of our agricultural systems, as well as further limitations on the supply of fresh water. And the fact that warming means more total energy in the atmosphere means we should expect more frequent and more severe storms; note that this can mean more severe blizzards in the winter as well as more severe hurricanes in the summer.

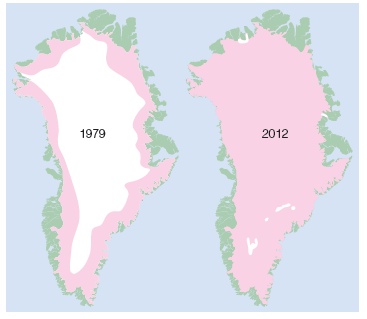

- Rising temperatures will cause sea level will rise. Even without ice melting, the fact that water expands slightly as it warms may make sea level rise up to about a meter (3 feet) by the end of this century. The added effect of melting ice could increase sea level much more. For example, recent data indicate that the Greenland ice sheet is melting much more rapidly than models have predicted. If this is the case and if it continues, sea level could rise as much as several meters by the end of this century—enough to flood regions populated by hundreds of millions of people worldwide. And while it’s highly unlikely that all the polar ice could melt in less than many centuries, remember this fact: Complete melting of the polar ice caps would increase sea level by some 70 meters (more than 200 feet). In that case, future generations will need deep-sea diving gear to visit places like New York City and San Diego.

Figure 5. These maps contrast the extent of the year-round Greenland ice sheet, shown in white, in 1979 and 2012. The pink area indicates the region in which at least some surface melting occurred during the warm season. While this does not mean that the entire ice sheet is at imminent risk of melting into the sea, it does show that melting is occurring at a much greater rate than most scientists had expected, which means sea level may rise more than previous estimates suggested.

- As the oceans absorb more carbon dioxide (an effect that is actually helpful in that it prevents all of our carbon dioxide emissions from remaining in the atmosphere), the pH of ocean water becomes more acidic. The overall effects of this ocean acidification are not yet well-understood, but some studies suggest that they could have devastating consequences not only to ocean species but to the commercial fisheries that are an important part of the global food supply. Note on geoengineering: Ocean acidification is independent of temperature; it occurs as long as we keep adding carbon dioxide to the atmosphere, even if the temperature does not go up. This means it throws a major wrench into proposed “geoengineering” schemes that suggest counteracting global warming with such things as spraying sunlight-blocking chemicals into the stratosphere or deploying giant sunshades in space; while these schemes could possibly slow the warming, they would do nothing about ocean acidification.

- And if all that is not enough to spur you to action, many scientists are concerned that continued global warming could lead to “tipping points” that might have even more severe consequences. For example, changes in regional climates might lead to sudden loss of forests that could amplify other climate effects, and changes in ocean temperature might cause major changes to currents (including the gulf stream) that regulate much of the world’s climate.

Key point for Question 6: Although there are uncertainties in the short-term (decades) consequences of global warming, there is no doubt about the basic underlying science. If we keep pumping carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, Earth will warm up significantly, with all the attending consequences listed above.

Question 7: OK, sounds bad. But is there really anything we can do about it? After all, even if we eliminated our own carbon dioxide emissions, the rest of the world — especially China and India — will keep emitting more.

Answer: Whatever happened to the “can do” spirit? Global warming is a problem that can be solved simply by replacing current energy sources with sources that don’t release greenhouse gases. This is not impossible — in a pinch, we could already do it with a combination of sources such as nuclear and renewables, and with a little investment we could tap much greater sources such as solar energy from space, new biofuels, and perhaps even nuclear fusion. The only missing ingredient is political will. The truth is, we are now getting our energy cheap because we don’t pay for the costs of its consequences (you can find a detailed analysis of these costs and potential replacement energy sources in Chapter 7 of Math for Life). If we factored those costs into the price — through a carbon tax, for example — I’m confident that the market would quickly find new ways of producing energy at low cost. And once we found those low-cost alternatives, China, India, and other nations would surely adopt them, since they’d be both cheaper and cleaner. After all, they want to survive too… (For a hilarious commentary on this topic, watch this Colbert video.)

Key point for Question 7: There is no cause for despair. The only major obstacle to solving the problem of global warming is the fact that we currently pay artificially low prices for fossil fuels, a result of the fact that users pay only the production costs while we socialize the costs of their consequences across society. (Yes, our current energy policy is socialism!) For those like me who believe strongly in market-based solutions, this implies that a substantial carbon tax might be all it would take to solve this problem and give us clean, cheap, and abundant energy for future generations. Call your representatives, and tell them the time has come for a carbon tax that accounts for the true costs of fossil fuels.

Bottom Line. So there you have it. There’s very little uncertainty surrounding the entire global warming issue, and what little there is concerns only whether we need to worry immediately or if we can afford to wait a few decades. In essence, the “global warming skeptics” (at least the ones who are serious scientists) are arguing that we should bet on the bad consequences taking longer to occur than current models predict, generally in hopes that future technologies might make it cheaper and easier for us to solve the problems in the future than to address them now. My opinion is that the risks of waiting are too great, and that the skeptics argument is rather like having a doctor tell you not to worry about quitting smoking, since we may find a cure for lung cancer before you die from it. To help you make up your own mind, I suggest that you take the “letter to your grandchildren test“: On average, no matter what age you are, your grandchildren will be your current age in about 50 to 60 years. So imagine writing (or actually write one!) a letter like the one below that will be placed in a time capsule for your grandchildren to read in 50 years, telling them what you did to help alleviate global warming, or why you decided that no action was required. Then ask yourself: How will they feel about the decisions you made?